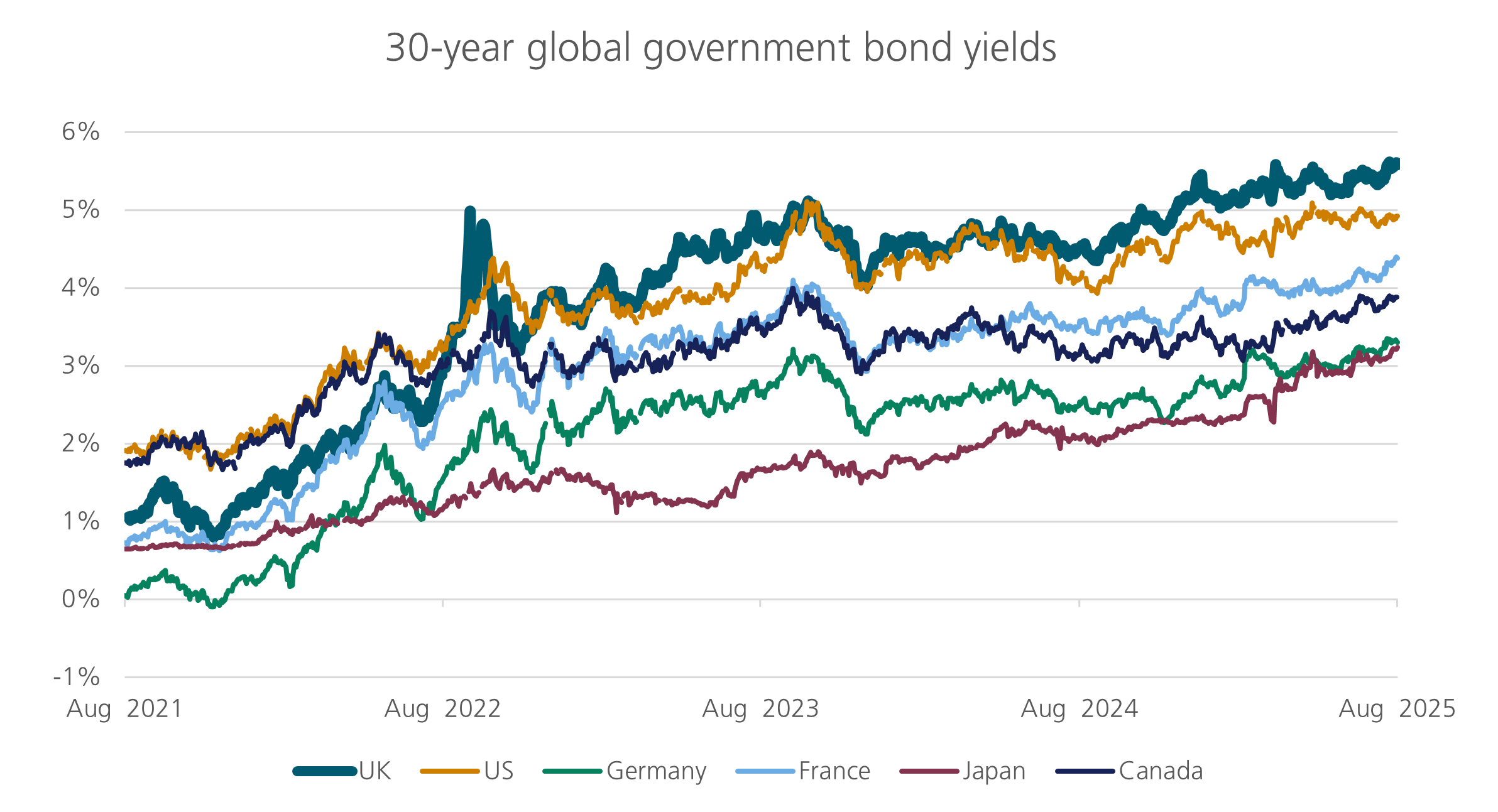

UK long-dated gilt yields have experienced a surge in recent weeks, with 30-year yields reaching 5.6% on 19 August, the highest among G7 countries and the highest since 1998.1 The sharp rise reflects a mix of global structural shifts and vulnerabilities unique to the UK. This week, we take a closer look at the drivers behind the move in UK government bond markets and what could help reverse it.

An unprecedented capital expenditure boom in AI infrastructure has reshaped how investors allocate capital. The world’s largest cloud providers will spend over $350 billion on artificial intelligence (AI) in 2025.2 Microsoft alone is allocating $80 billion to expand Azure's AI capabilities, while global AI infrastructure spending could reach $900 billion annually in 2028.3

This massive capital reallocation signals a structural shift toward higher long-term growth expectations. Total spending on AI infrastructure is contributing an estimated 0.75-1.5% to US GDP growth in 2025.4 This makes holding long-dated government bonds – traditionally seen as a safe asset class – less attractive. Unlike traditional investment cycles, AI spending appears largely decoupled from interest rate sensitivity, making it harder for central banks to manage future policy.

Compounding this global shift is the resurgence in defence spending. NATO's commitment to 5% of GDP defence spending5 (3.5% core defence spending plus 1.5% on infrastructure and digital resilience) adds further pressure to government debt. This is exemplified by Germany's €1 trillion defence and infrastructure package.6 The convergence of massive private capex and rising defence spending creates unprecedented competition for global savings. This in turn has driven term premiums – the extra return investors demand for holding long-term government bonds compared to short-term government bonds – higher as governments and corporations bid for the same investment pool.

The result is a fundamental shift where government spending – rather than monetary policy – drives economic activity. Rising long-term yields now happen alongside strong equity markets, indicating that markets price persistent growth and higher equilibrium rates rather than monetary policy expectations. This environment favours risk assets but penalises duration, particularly in fiscally vulnerable markets like the UK.

While these trends affect bond markets globally, the UK is particularly vulnerable. The UK's fiscal deficit of 5.3% of GDP ranks among the highest in advanced economies, exceeded only by the US (6.6%) and France (5.4%). However, unlike these peers, the UK lacks structural supports – it does not have the dollar’s reserve currency status, and it has no implicit backstop Eurozone countries have through the European Central Bank (ECB) and German fiscal strength.

This vulnerability is compounded by heavy reliance on foreign financing, with over 30% of gilts held by overseas investors7, well above the 18% average for advanced economies. A significant number of foreign investors own US and German government bonds (23% in the US and 26% in Germany) but both benefit from the structural safety pillars mentioned above.

Domestically, sticky inflation is exacerbated by recent policy choices. UK inflation – which has proven significantly stickier than peers – accelerated to 3.8% in July 20258 compared to 2.7% in the US9 and around 2% in the Eurozone.10 Services inflation remains elevated, sustained by robust wage growth and tight labour markets, while housing, utility, transport costs (especially airfares) and food price inflation remain high. These structural issues – particularly higher energy and utility costs – affect the UK more severely than other European countries because of different energy market structures.

Labour’s first Autumn Budget from October 2024 has also played a role in recent inflation readings. Large real minimum wage increases along with an increase in employer National Insurance contributions created significant cost pressures for businesses, especially ones with lower median wages in the service sector. These businesses, such as supermarket chains, along with those in leisure and hospitality sectors, ultimately passed these higher costs onto the end-consumer. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) explicitly noted that the Autumn Budget measures would push CPI inflation back up to 2.6% in 202511, driven by persistent wage growth and fiscal loosening, although that now looks like an underestimation.

All told, stubbornly high inflation limits the Bank of England (BoE)’s ability to cut rates more aggressively.

In June 2025, Chancellor Rachel Reeves introduced a £5 billion welfare-savings package, only to see over 130 Labour MPs rebel and overturn it, citing its harsh impact on vulnerable households. This rebellion underscored the government’s limited appetite for spending cuts, making tax increases the main lever for fiscal consolidation. The bond market reaction to Reeves’s suggested removal illustrated just how pivotal investor confidence has become. As news swirled in June of a potential cabinet shake-up, 10-year gilt yields jumped to nearly 4.90%. Once it was confirmed Reeves would remain chancellor, gilts rallied for four straight sessions and yields fell by over 35 basis points. Clearly markets trust Reeves’s stewardship more than any alternative, and the government cannot ignore bond markets without risking funding costs increasing significantly.

Expected OBR downgrades to growth and productivity now imply a fiscal shortfall of around £20 billion in the coming budget. This will likely force the government to raise taxes despite manifesto pledges. Potential measures include higher capital gains rates, new levies on inheritance, reforms to pension tax relief, and property taxes.

Longer-term, there are other options to balance the budget, however. The UK tax system is notoriously complex relative to other advanced nations. This stifles labour mobility, creates inefficient uses of resources, and ultimately limits productivity. Potential tax simplification reforms could deliver significant productivity dividends by reducing the administrative burden on businesses and enabling more efficient resource allocation. Such structural improvements could help stabilise the OBR's productivity and growth assumptions without requiring significant additional tax increases, potentially creating a cycle where tax reform supports the very growth needed to balance the public finances.

The BoE’s August 2025 meeting disappointed markets seeking clearer signals on reducing active quantitative tightening (QT), particularly for long-dated sales. Despite acknowledging that QT has increased the term premium by 0.15% to 0.25% (up from previous estimates of 0.10% to 0.20%), the BoE provided no commitment to pause or reduce long-dated gilt sales. The BoE deferred the decision to its September meeting, maintaining the current £100 billion annual QT pace. Markets had expected the BoE would provide a stronger signal that it would ease or halt long-end sales, which has in turn contributed to the upward pressure on long-dated yields.

Pension fund demand for long-dated gilts has undergone a fundamental structural shift in recent years, accelerated by the September 2022 volatility during Liz Truss’s short-lived tenure as prime minister. Also referred to as the Liability-Driven Investment crisis (LDI), UK markets faced turmoil in September/October 2022 following the release of Truss’s mini-budget, which triggered sharp government bond yield increases. UK defined benefit schemes have reduced their direct gilt holdings by approximately £210 billion since 2020.12 This has been driven by a combination of factors, including lower demand due to the shift towards defined contribution schemes, lower leverage levels to withstand potential rate increases and a shift towards long-dated infrastructure assets to better match liabilities. As a result, markets now depend heavily on foreign investors and hedge funds, which are less stable and more price-sensitive than traditional pension fund buyers. This has reduced market resilience and increased volatility.

Responding to market pressures, the UK Debt Management Office (DMO) significantly reduced long-dated gilt issuance earlier in the year. The allocation to long-dated gilts was cut from nearly 20% of total issuance in the Autumn 2024 statement to just 10% in the April 2025 revised remit. This reflects both market pricing pressures and the DMO's recognition of reduced institutional demand for long-dated paper. However, this tactical retreat doesn't solve the underlying problem – it simply concentrates the duration risk in a smaller pool of securities while the government still needs to fund its deficit somewhere along the yield curve.

UK long-dated yields are high because global term premiums have risen, and the UK’s own fiscal position is precarious and does not have structural benefits enjoyed by the US or Eurozone countries. Sticky inflation, productivity losses in the UK, and technical drivers to do with QT and the shift in pension fund demand for bonds add to the challenge. But markets can turn swiftly. We outline the catalysts for a potential reversal in gilts below:

While markets remain under pressure, a combination of inflation relief, credible fiscal action and better policy signalling could help restore confidence in long-dated UK debt.

[1] Bloomberg

[2] Big Tech's AI investments set to spike to $364 billion in 2025 as bubble fears ease

[4] gdp2q25-adv.pdf

[5] NATO’s new spending target: challenges and risks associated with a political signal | SIPRI

[6] Germany’s Merz secures breakthrough on gargantuan spending plan – POLITICO

[7] Debt_Management_Report_2025-26.pdf

[8] Office for National Statistics

[9] Bureau for Labor Statistics

[10] Eurostat

[11] Economic and fiscal outlook – October 2024 - Office for Budget Responsibility

[12] Bloomberg Intelligence - UK Defined-Benefit Pension Rundown Cuts Gilt Demand

LGT Wealth Management UK LLP is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority Registered in England and Wales: OC329392. Registered office: 14 Cornhill, London, EC3V 3NR. LGT Wealth Management Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Registered in Scotland number SC317950 at Capital Square, 58 Morrison Street, Edinburgh, EH3 8BP. LGT Wealth Management Jersey Limited is incorporated in Jersey and is regulated by the Jersey Financial Services Commission in the conduct of Investment Business and Funds Service Business: 102243. Registered office: Sir Walter Raleigh House, 48-50 Esplanade, St Helier, Jersey JE2 3QB. LGT Wealth Management (CI) Limited is registered in Jersey and is regulated by the Jersey Financial Services Commission: 5769. Registered Office: at Sir Walter Raleigh House, 48 – 50 Esplanade, St Helier, Jersey JE2 3QB. LGT Wealth Management US Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority and is a Registered Investment Adviser with the US Securities & Exchange Commission (“SEC”). Registered in England and Wales: 06455240. Registered Office: 14 Cornhill, London, EC3V 3NR.

This communication is provided for information purposes only. The information presented is not intended and should not be construed as an offer, solicitation, recommendation or advice to buy and/or sell any specific investments or participate in any investment (or other) strategy and should not be construed as such. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of LGT Wealth Management US Limited as a whole or any part thereof. Although the information is based on data which LGT Wealth Management US Limited considers reliable, no representation or warranty (express or otherwise) is given as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in this Publication, and LGT Wealth Management US Limited and its employees accept no liability for the consequences of acting upon the information contained herein. Information about potential tax benefits is based on our understanding of current tax law and practice and may be subject to change. The tax treatment depends on the individual circumstances of each individual and may be subject to change in the future.

All investments involve risk and may lose value. Your capital is always at risk. Any investor should be aware that past performance is not an indication of future performance, and that the value of investments and the income derived from them may fluctuate, and they may not receive back the amount they originally invested.