This summer, news coverage on China has turned quite negative.

Some recent articles allude towards a potential “Japanification” of China, a term which describes the so-called “lost decades”, when the stock and property bubble of the 1980s led to persistent weak growth and multidecade deflation.

Given both countries are focused on manufacturing and China has seen its property market deliver strong growth over the last decade, it not surprising that this narrative has gained traction. However, while these make attractive headlines, there are some clear differences that should be acknowledged before relying on past experiences.

Looking back over the last few years, despite COVID emanating from the Wuhan province and China becoming the first country to resort to lockdowns, the subsequent period proved economically favourable.

With rolling lockdowns across the world, demand for services fell precipitously while goods demand soared. People cancelled holidays and spent more time at home. As a result, spending shifted towards high value household goods, electronic equipment and low-ticket items such as PPE.

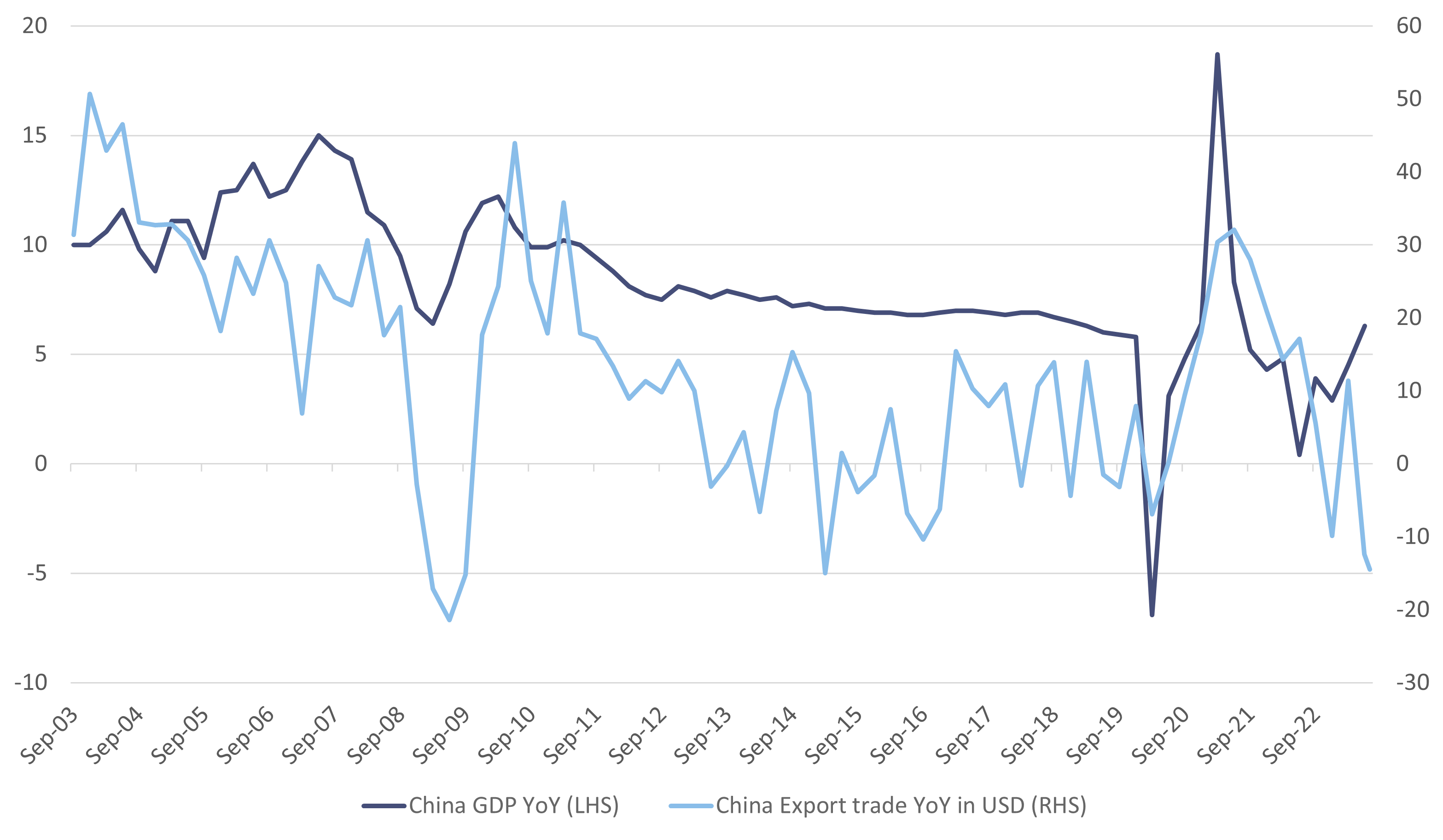

Consequently, the value of Chinese exports soared, driving a sharp economic recovery.

This led the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to shift focus from purely growth towards more qualitative objectives in October 2020. China’s strong growth in the aftermath of the global financial crisis was fuelled by debt financed stimulus, mostly directed towards massive infrastructure and housing projects. As the move towards cities gained traction, property prices rose and prompted the CCP to start clamping down on property as an investment and tighten standards.

While Japan allowed their property bubble to grow for a few years, China sought to control property markets promptly, an effort to avoid a similar outcome to its neighbour. The CCP tried to navigate the tricky balance of moderating leverage in the sector without stifling growth.

However, given the amount of debt misallocation that fuelled the infrastructure boom, this led to a material tightening of credit conditions. As such, when the country went into lockdown, deposits dried up, proving disastrous for housebuilders and prompting a liquidity crisis. This ultimately led to the property giant Evergrande declaring bankruptcy in the US and, more recently, concerns building around Country Garden.

The CCP has been trying to restore confidence in its housing markets by loosening standards, but so far there is little sign of this materially changing the fortunes of these companies.

Problems in China started when most of the world looked beyond the pandemic towards normalisation in 2022, and when consumption moved from goods towards services. This led to a sharp fall in exports globally.

At the same time, China maintained its ‘Zero-COVID’ policy, curtailing domestic demand up until the end of last year. The re-opening led to an initial sharp bounce in demand but faded quickly. The most recently reported youth unemployment data shows a concerning rate of 21.3%, raising concerns of further export malaise. When China simultaneously announced that they would stop publishing unemployment data going forwards, this did little to comfort international investors. While this all paints a bleak picture, there are some important mitigating factors to consider.

The average Chinese consumer still has an enormous amount of unspent savings that has accumulated over the course of the pandemic. This in essence shows that the malaise is heavily influenced by consumer confidence.

As the CCP moved from growth targets to qualitative measures, this involved crackdowns on the education sector and tech giants, prompting sharp declines in the share prices. Looking further back, realising the aging population trends, China sought to move away from its one child policy, yet this behaviour appeared to have become culturally ingrained and didn’t result in any material change.

In terms of the property sector, the line from the CCP was that property is for living, not speculation. This had recently been omitted before being reiterated earlier this week. With the wealth channels of property and equity markets being targeted, it is not too surprising to see that desire to invest has weakened.

As China remains a controlled economy, however, it can offer more targeted stimulus and intervene fiscally to restore confidence by taxing savings and encouraging investment.

Furthermore, during the pandemic it invested heavily into electric vehicles as it attempts to move the economy away from low value exports. The pace of the change is remarkable, with China overtaking Japan in terms of car exports. Although it is worth noting that this transition is likely to have an initial economic cost.

The stimulus so far has been limited, as China is taking a measured approach to reduce financial risks rather than swiftly changing course. Earlier this week, People’s Bank of China reduced its one-year loan rate by 0.1% to encourage further consumption. At the same time, its intervention in currency markets to announce a higher fix shows a desire to stop the currency from depreciating further, backed by reserves in excess of $3 trillion.

Despite China having the means to reverse this crisis, to date it remains hesitant. If it were to announce larger stimulus packages, this would put further pressure on its currency, given where central bank interest rates are elsewhere. As such, China faces the difficult balancing act of modestly propping up its economy while trying to prevent further currency depreciation.

This communication is provided for information purposes only. The information presented herein provides a general update on market conditions and is not intended and should not be construed as an offer, invitation, solicitation or recommendation to buy or sell any specific investment or participate in any investment (or other) strategy. The subject of the communication is not a regulated investment. Past performance is not an indication of future performance and the value of investments and the income derived from them may fluctuate and you may not receive back the amount you originally invest. Although this document has been prepared on the basis of information we believe to be reliable, LGT Wealth Management UK LLP gives no representation or warranty in relation to the accuracy or completeness of the information presented herein. The information presented herein does not provide sufficient information on which to make an informed investment decision. No liability is accepted whatsoever by LGT Wealth Management UK LLP, employees and associated companies for any direct or consequential loss arising from this document.

LGT Wealth Management UK LLP is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority in the United Kingdom.